Feel Free to Disregard Entirely – Unsolicited and Ultimately Untimely Advice to College Students That Are Sometimes in My Class

John den Boer

Adjunct Faculty, Department of Psychology

The University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee

College Students (at least those in my class, albeit at times) –

I truly hope this finds you well.

I spoke in class about two weeks ago about the need to be in tune, and possibly accelerate, the process of transitioning into your future professional self. I indicated that this was integral to your development as both a person and evolving professional. I may have use words like mindful and intentional; possibly even strategic. Now that I think about it, I may have referenced the unconscious. For this – as well as the length of this (sprawling, unwieldy?) diatribe, I apologize.

For reasons that are entirely unclear to me, I decided to expand on this by offering an unwieldly yet comprehensive and entirely unsolicited framework by your life could be lived.

After reading this, maybe you’ll decide that while a life could be lived in this manner, the life in question is decidedly not your own. You may decide to entirely disregard this or not to read it at all. That’s ok, if not totally cool. Really. The key is -really is – to think better, to think well, and to think practically, strategically, and intentionally.

Probably without you knowing, all of you are already doing this to some degree or another, but, in my opinion, it would be to your advantage to consider paying closer attention and potentially monitoring this process, both academically and psychologically. The point I will try to make (i.e., belabor) is that the two are intrinsically intertwined and that your personal development needs to come ahead – in fact, preempt, your professional development.

Much of this stuff might be obvious and/or apparent. It’s probably stuff you already know but, for multiple reasons or another (see below for my hypothesis) you’ve haven’t acted on it. I don’t know exactly why I decided to write such a lengthy response – at a conscious level I think it’s an attempt at coalescing some scattered thoughts that I have, up until previous, just ranted about in class. I may be feeling, that despite all my impassioned and somewhat desperate attempts at motivating you, I have failed in imparting practical advice and listened in a deep and intentional way. Maybe I just feel alone. I’ve been yearning for solitude and love watching the sunrise, so I’m not sure why I would feel like that. But maybe that’s the point.

Despite the inherent flaws in my logic and the tangential-ness and rambling nature of my advice, I truly and wholeheartedly want for you what I have been able to achieve and what I prize most securely and protect most fiercely: freedom. As you may conclude after reading, this is a freedom that many of us have never known and most likely never knew existed. It’s a simple but not easy freedom that I believe we all deserve. I don’t mean to be too Jungian, but it’s also a collective freedom. I would say it’s hard fought, but I don’t think that we know there is such a battle to fight.

Freedom starts, most foundationally, from beginning a (not the) process of coming to know yourself as you are evolving. This is difficult to do, as, whether you like it or not, you’re experiencing an immeasurably intense period of personal and professional growth, one that is so awesomely terrifying that, at this very moment, you’re undoubtedly denying the gravity of this disjointed evolution. I know it sounds like a banal platitude. That’s what I thought too.

Education, for all it’s great and abstract qualities, suffers from a kind of distant narcissism that tends to isolate people like you. At least I think so. Higher education is both enticing and infuriating in this respect. At the risk of sounding narcissistic myself, we should have begun teaching you this long ago. Teaching you how to know yourself; how to discover your voice and your vision and how to distinguish it (in the purest form of signal detection theory) from the noise of everybody’s else’s thoughts masquerading as your own. I assert to hear your true self clearly is paramount now.

Psychology might be the worst example of double-speak of all professional disciplines. The disjointed and often-bewildering dogma that purports and promises self-growth (e.g., we are all beautiful and unique individuals) while at the same time providing an alluring miseducation (e.g., if you study this, get a good grade in this, you will grow as a person).

Just today I again recited the quote from Carl Rogers that ran counter to this, remarking that it’s dissenting stake was the reason I got into Psychology. I didn’t expect you to remember it, so here it is again:

“The touchstone of validity is my own experience. It is to experience that I return again and again to discover a closer approximation of truth as it is in the process of becoming in me.”

I still like it and still believe it.

Students (well, one) told me that my rants (I call them “lectures”) are “good” (I had the impression that her eyes were using air-quotes) and all, but don’t help her in the moment, when she’s trying to problem solve her way through the mess of life. She’s totally right, but, in my (self) defense, I’m not alone.

It’s the Spring semester and the buds have just shown through the sloppy and yellow Wisconsin grass, so I’m sure you know this by now, but college professors often pride themselves on “teaching students how to think.” I’ve repeated this statement many times in my almost 15 years of college teaching thus far (I think I said it last week more than 5 times). I believe this statement to be true, but feel what must come before it is more important: learning how to think about yourself.

So let’s get on with it: just exactly how do you think clearly about yourself? I might add, just for the sake of confusion, you probably shouldn’t. Seeing yourself perfectly clearly can be detrimental to your mental health (research has robustly shown that non-depressed people have a modestly over-exaggerated view of themselves). Therefore, and I hate to sound like a Psychologist, but I recommend having a soft and perhaps uneven focus.

In order to do this, I suggest the following practical steps:

- Visualize what you want your future life to be (keep it personal at this point, not too far into the future – 5 years is a good time frame). Keep it realistic, yet aspirational. Strive to be better than previous generations (no disrespect to your elders). Having a person that you emulate can be very helpful, but is ultimately unnecessary.

- Search for jobs in a few fields you are interested in upon graduation. Indeed or other search engines can be a good start for this.

- See if these jobs fit your future life goals, etc. The easiest way of doing this is to use your aspirational writing – See Visualization exercise above.

- See if these jobs fit your FUTURE, aspirational budget (not current).

- These jobs need to be in a field that you are passionate about (hopefully, really passionate about), but they need not (almost definitely will not) be your “dream job.”

- Revise jobs as your life goals/aspirations change. You will change a lot during this time, and your goals and objectives should change as you change. Again, you have to realize how and when you are changing and that’s hard.

- Given above, see if you are on the best educational path to meet your life objectives. The key is not to be “right,” but to develop the diligent and compassionate tracking mechanisms of this now.

- If you’re not on track, that’s OK, please consult your educational advisors, teachers, etc.

- Please keep close tabs on this process. Again, you’ll have to make multiple changes as you change (nothing wrong with this). Being flexible yet having a structured set of personal and professional goals are valuable attributes in this process.

If you’re human (I’m assuming you are), you cannot do this alone. You would do well to have both accountability partners and emotional and probably financial support. It’s unlikely you have all three (if so, practicing gratitude may be in order) and, if not, pleasure work diligently to obtain the sources of structured and predictable support. Highly suggest being such a support for others as well.

It is/will be hard, but please be completely honest and transparent with these trusted individuals. Good accountability partners are honest, direct, and caring; they do not automatically take your side and should firmly counter gaps in your logic and play “devil’s advocate” often in your major life decision making. Maybe it’s obvious (but worth saying), but do not enlist a past or current romantic partner, really close friend, or someone you are consistently in close proximity with, as an accountability partner. You want someone who is somewhat distanced from you, both physically and emotionally. A trusted fellow classmate or colleague may be a good resource. Again, a solid karmic expectation is that if you serve as an accountability partner for them they will, in turn, serve as one for you (and vice versa). Faculty mentors may also help, but cannot effectively serve this role.

Having multiple accountability partners is a good thing. No matter who you are, you undoubtedly need more support than you realize. Going through the process of personal and professional self-discovery alone is not a sign of courage and strength, but rather stubbornness and stupidity. You will undoubtedly fail. We are, by definition, blind to our blind spots.

Despite what the media and movies have shown you, this is definitely one of the most difficult transitional times of your life. It’s made more difficult because you are never told it is really really hard and that the feelings you are experiencing during this time (loneliness, disengagement from yourself and others, identity shifting, role confusion) are ones that all college students are experiencing, whether they know it or not. It’s even more difficult when you consider you are undergoing a really heavy transition as you move from your current self (really selves) to your future selves on the bedrock of often unstable financial and professional footing. Additionally, the fact that this happening at a deep (often unconscious) personal level, but is also happening as you begin, probably for the first time in your life, to encounter the proverbial and disastrous (e.g., defeating) question “What am I going to do with my life?” produces in all a sense of existential dread that is so deeply felt that we often deny it through alcohol, drugs, and other unsafe and self-sabotaging behaviors.

Although I often will joke or lie about my college experience to others and to myself, consciously and unconsciously. At least I know I’m lying. In my quieter moments I do remember this being a very stressful time of my life, full of promise, opportunity, and fear of the unknown. I felt disconnected from both the things I had known and the things I was yet to know. There was a lot of pain, which I coped with by using very undeveloped and unpracticed coping mechanisms. I’ve come to believe this process – although both foundational and necessary – would have been helped (and eventually was) by more social connection, counseling, and overall recognition of how difficult this transition period time was. I also could have used some financial stability. If you’re reading this – and still human – you probably relate. Almost all (i.e., all) college students do.

I am pleased to now realize that many colleges, including UWM-Waukesha, offer free and accessible counseling services. Please consider using them (man have I belabored this point), as getting mental health services will, unfortunately, never again be this easy to access. Even if you’re not acutely in pain, please consider using these services to better your life and the lives of those around you. There are also other counseling services and groups available for those that are truly earnest about improving their mental health; please dive courageously into them. If no such group/program exists for your challenge/pain point, help start one. College is an awesome place to do this. In short, please don’t let your psychological blind spots and old tapes impede your educational and professional success.

At this point in your life you’re probably dealing with all kinds of foundational and deep stressors: finances, living situation, relationships (not an exhaustive list), which you’re doing your best to handle in an adult-ish type way. I truly empathize with these difficulties and remain conflicted between the part of me that wishes you didn’t have them and the other part that knows you should. I bet, more so than most people, you’re struggling with embracing your creative and unique intelligence and molding it into your professional identity. Again, platitudes, but that’s OK, good, about right, yada yada yada.

As you’ve probably gathered by now, I have no original thoughts on this topic, only to suggest that stepping into your greatness as soon as possible (even when it’s not possible), is vital. Fortunately, William James (remember him – “Founder” of American Psychology – yada yada yada) had some thoughts on this growth predicament; you may not remember (that’s cool, I only yelled – enthusiasm, not anger – to you about this. James’ whole shecht sort of went like this: fake it to you make it. No, really. What James didn’t know, almost 100 years ago, was that his theory (later incorporated into the James-Lange theory) would be applied by a zany (some say – perhaps rightfully – crazy) Psychology Professor (an adjunct!) in a perhaps-misguided attempt to give perhaps-entirely incorrect and certainly unsolicited advice to his students.

I could go into all the ins-and-outs of the James-Lange Theory of Emotion, which would make me feel smart (which is enticing, because I don’t feel this very often) and create further intellectual distance between us, but I will simply repeat the underlying message:

Act first, feel second.

Ace before you feel.

Then you’ll feel like acting.

This is, to me, one of the most revolutionary and underrated messages in Psychology and one of life’s greatest lessons.

It’s also a message both humans and the media almost-always get incorrect: we receive constant communication– both consciously and unconsciously – that we feel a certain way, then we act. This is exemplified in statements like “I don’t feel like ___” and the yawning, almost inevitable, non-action that follows. This cascades into the almost-inevitable, wildly inaccurate, although altogether enticing assumption that waiting until you feel like doing something will lead to the target behavior being initiated, the task being done.

This fallacy, perhaps unconsciously, forms will ultimately lead to non-action. You know this: For things that are hard, we almost never feel like doing it. James knew this too, and the simple brilliance of his theory is obvious: we only begin to embrace the feeling once we begin to act. The relevance to you as you begin to step into your professional role is equally transparent:

Start acting professionally now. Start acting brilliant now. Claim your place. Now.

As the absurdly great Gary Bucey once taught me: N.O.W. = No Other Way.

The fact that the James-Lange theory is empirically-validated yet incomplete, and that it does not apply in all instances, and that there is more empirically-validated and comprehensive and modern theories should not dissuade you of this simple dictum. N.O.W.

To put another way: Behavior first, Biology second (I made that up); we act, then we feel like acting more, then we act more (insert basic circular diagram here – no need for a Venn diagram).

Back to transitions for a bit…basically, transitions are really hard. As I’m writing this I realize that I don’t have a lot of great advice on transitioning and probably used what I have all up above, so I’ll share my experience in a “hail-mary” attempt at helpfulness.

Don’t ask “helpful for whom.”

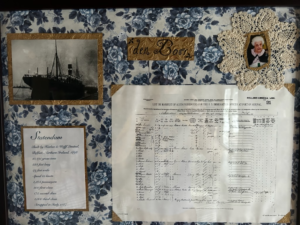

As I was going through graduate school, I came to know a bit about my family’s journey to the United States. For multiple reasons – some I’m still trying to figure out – it has come to resonate deeply within me. During times of struggle/darkness during college, I often thought about my Great-grandmother, Catherine (“Katie”) Trass who passed away at age of 101, who 95 years prior to her death got on a ship from Holland with all her family and left across an ocean into a void, into a world, she did not know.

Conditions were so bad in Holland that her father and de facto family leader, John Trass, decided to risk the lives of his wife and 7 family members to undertake the nervous voyage to America. I asked my Grandmother about this last week. Why she said, rather dryly: “They were eating their shoelaces, and there were only so many shoelaces.”

I repeat this story, this experience, not because it is unique. Quite the opposite: I repeat it because it is not unique or special at all. Many of your families were and still are bound by shackles: physical, economical, and political. You are probably not aware of these chains, some people would say blissfully so, but they’re wrong.

My family is bound by less shackles.

But only because I broke them – kinda.

Talk about entering the void. When my Great-grandma and her family came to Ellis Island, some two months later, she had seen death and severe illness first-hand. When her abstract dream was fully realized by the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island, her brother (who was developmentally delayed – not sure what they called him back in the day) was denied entry. He was not alone.

My ex-wife made this collage:

I stood where they stood.

During my first visit to New York. I stood in the same room that the testers administered their fatal “intelligence tests.” Surprisingly, alluringly, beautiful, the light streaming in from above (the light Manhattan skyscrapers couldn’t keep out); one door to freedom, one door to hell.

The tests, the ones that send Jakob back.

And the younger John Trass, who had to go back with him.

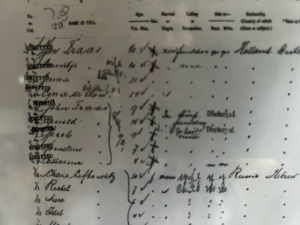

I imagine you’re putting two and two together, because you’re smart and capable and yada yada yada. Because of his failure on these tests, Jakob was sent back across the Atlantic; an older brother was send back to Holland with him; the family never saw them again. This is depicted in a copy of the ship manifest’s below. I look at the stamp, stare at it. I pay particular attention to the Admitted Stamp, then the fatal change, right on top and to the side but not entirely excluded. Deported. Discharged. It’s been 10 years and I can still see the change, more so feel it. It’s in me (see below). The same way that your trauma is in you (see below).

They were in America and they endured hardships, eventually (finally) finding factory jobs in Northern Wisconsin. Again, not special or unique. Your families had worse. This has and still affects you (see below).

When I was younger – somewhat about your age – I questioned why he would take such a risk. Who was this decision really benefitting? As I became older, I became more sure why he did it; now that I’m a father, I’m certain of it. And in the truest and boldest sense of the American Dream I’m certain of why every generation subsequent to you fought – and continues to fight – to survive and thrive in an often-hostile world. It should be obvious by now what the answer is:

You.

Well, not exactly. Like anything in Psychology (humans), it’s not that clear cut.

The possibility, the raw inevitability, of You.

Just as I imagine my forebearers shivering, weak with malnurtrition and sickness, wet in the hulls of boats, I attempt to sit with the realization of the hardships endured for you – and I for tht matter – to be here. I try to sit intimately, imaging these types of moments. I imagine that these rather privileged immigrants, those that had it better than your forefathers did – were in conflict. I know that they were, at least that’s what I was told/read/studied/learned/forgot, but never really/learned again.

It is hard, very hard, but essential to be still with the humbling realization that as hard as this transition is, theirs was much much harder. And more than that, their transition gave birth (quite literally) to yours. Like this sun (son), peaking.

You.

I’m sure it’s difficult to accept the gravity that this transition you are currently gravitating towards and impersonating your way through is the predicating key that unlocks your future family, your real and triumphant victory. The success of these college years (both personally and professionally) will be necessary to the mental health and quality of life of all your subsequent lineage.

You know that and that knowledge makes it difficult to sit with.

I’ve tried to convince you – and maybe lied to you in the process – that your greatest fear is your own power. Your own beauty.

It’s hard to imagine that when my Great-Great Grandfather, the leader, John Trass, made the decision to risk the lives of his entire family to immigrate to the United States that he could imagine his Great-Great Grandson would be communicating virtually (?!) to his students about his rather insane decision. Equally, I’m sure he never contemplated that I would be using his story to relate it to the story of students that were born some 100 years after, those that live in a world both the same and vastly different from anything he or his forebearers knew. He didn’t know that his son, his namesake, would leave him along with Jakob. He should have but how could he.

I’m also confident he couldn’t haven’t imagined how this story would have turned out, just as you little way of knowing how the actions you take now, both inside and outside of this University, will affect the lives of your Great-Great (yada yada yada) Grandchildren. You should but how can you.

How could they.

Research- the type of research you should know – now tells us that DNA is much more malleable than we previously thought and incorporates elements of all individual’s personal and family psychology, including trauma, hopes, and dreams. For all of us, this includes “family traits” that we have held in both high and low esteem, the talk of rumors and destiny. Destructive cycles you may wish to break.

The scientific community has discovered and has begun to highlight the genetic transmission of trauma (e.g., Bowers & Yehuda, 2015; Daskalasis et al., 2020; Yehuda and Lerner, 2018). To be clear, these findings underscore that the exposure of trauma changes not only the genetic structure of those experiencing it but changes the genetic structure of all subsequent offspring.

Additionally, we also know that in addition to changing DNA/RNA and mitochondrial dysfunction, we also know that exposure to trauma changes the brain functioning of subsequent generations as well. Yes, the brain reorganizes/remodels itself after trauma, but, again, not just in the individual experiencing it, but also in all subsequent generations. You. Oh yeah, here’s the reference (Alhassen et al., 2001) – remember that you can put et al. if there are 7 or more authors. At least for now.

I’ve told you – redundantly and often pedantically – that this is a tremendous opportunity and not a fatalistic curse. But I’m sure you’ve by now come to the all-too-accurate assumption that it is both. You’re smart and capable.

In fact, I’ve told you a number of things about this topic, now that I remember.

1). All trauma is genetically transmitted.

2). All trauma re-organizes (mutates) one’s genetic code and affects it’s downstream organs, including the brain.

3). We make decisions, often reflexively and unconsciously, on the basis of this trauma.

4). you can change this cycle.

5). Therapy, coupled with awareness and better life choices, will help, but you must approach this with a degree of seriousness and diligence that borders on Ahab-like zealousness.

6). This is really really hard.

7). You will change.

8). You need support during this change.

9). This is your most essential and greatest life’s work.

10). You must do it.

11). It will be worth it.

I was planning on showing you a graph here, but it does not appear needed.

The research above significantly highlights the strong need to make both personal and professional decisions to better your life. In doing so, you will undoubtedly benefit others, most importantly your genetic offspring and the overall community.

Even if you don’t choose to have children of your own, your ability to break the chains of past detrimental personal and family cycles will be paramount in the improvement of a better world. Hopefully, in reading the above, you recognize that this is not a hypothetical platitude, but something real, concrete, and embedded in the very cell of our being. Definitely in you.

Speaking of research, last week we reviewed social psychology. Not a lot of you were in class that day. That’s cool. I told you attendance was not graded, in a perhaps misguided attempt at moulding you into a more independent decision-maker and a stronger accountability partner to yourself. At least that was the idea.

It may work.

I emailed you some of the video links – some of these links are the same videos that I watched as an Introductory to Psychology student at Carroll in 1997. As I re-watch them, they are more important and disturbing to me now than they were then. Probably more disturbing.

I think I’ve told you that perhaps the most important thing that Psychology does is empower one to understand not just the behaviour of others (difficult) but also your own behaviour (very difficult). I believe the information contained in this short chapter is essential to you living your life in a meaningful and fulfilling way and also benefitting the human and non-human community in which you live. I think you believe me.

I have urged you to take the following clips very seriously. I even wrote the following: “…Please keep in mind few people ever think they are ‘bad,’ and, in many ways, they are not. Rather, the history of this world shows that good people will do very bad things when under the powerful social constraints of obedience, role persuasion, and conformity.’ I am surprised that I wrote that (it’s good). I still believe people are basically good, which is even more shocking.

I probably believe that people are more capable of doing more horrible – almost incomprehensible – things more easily. Sad but true.

I included some video links – I sincerely hope that you watch them. Maybe if you’re reading this (still!) you will watch them and see how terribly flawed and vulnerable humans are.

I hope that you watch these links, but I sad you need to. That’s what being a parent feels like; a beautiful and at times unexpected melancholy.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F4txhN13y6A

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rdrKCilEhC0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TYIh4MkcfJ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BdpdUbW8vbw

I like some of my writing. I wrote further: “Contained in these social psychology experiments and others are tremendous power to do both good and evil. It will always be your moral and ethical responsibility to use this knowledge for good to help better the world. As shown through this chapter and the above video clips, the key – somewhat paradoxically – to do this is to not trust yourself to be and do good always, but to set up your social constraints and behavior funnels to promote and reward good behaviour and punish harmful behaviour.” Pretty decent. I concluded with: “From my experience, this is simple but not easy and perhaps your most vital task as a living being.”

I did not tell you that I failed in this – many times – and have succeeded in getting better but have not and will not totally succeed. I have not told you that all humans are this way. Jung did. Collective unconscious. Remember?

I’ve recently began attending a Universalist Church. During the sermon this past Sunday our Pastor/Chaplain/Minister (I’m new to Universalism) was telling the story of Moses and the Israelites crossing the Red Sea. The way I remember it, of no fault of those that taught it to me, was that Moses held out his staff, maybe said a prayer and/or spoke aloud to God (?), and the seas (Red) parted. That, at a very high level, is accurate/correct. What I learned two Sundays ago was a little-known, often left-out, but integral (to me, to you) part: before Moses struck down his staff, and Israelite – I forgot his name- first strode into a (non-parted) Sea. As he began drowning, Moses cried out to God, asking God to perform the miracle that we know so well. Why is this so important? Because, even in Biblical times, long before William James or Psychology or Academia, there was a rather unconscious knowing that action preceded confidence. That you had to prove it to yourself before your confidence grew. Jump before the net opens.

That you needed to act before the miracle.

At the risk of sounding like Malcolm Gladwell, this is where the first “fake it to you make it” was recorded (no offense to Malcolm Gladwell); the first record in the first book ever recorded. I’ll phrase it another way (although not original): “Act as If.” William James knew this, even though he has no or very little official predecessor or predicate prior. I’m not saying Moses or Jesus of God wasn’t official.

You get it.

But not really.

I’m not sure what you believe, but I consider it one my greatest triumphs as a homo sapiens that I still believe the thing that got my into Psychology to begin with: the humanistic belief that we all start good, and given generally healthy conditions, we basically gravitate toward good. It’s an easy concept to believe when you’re younger and a fairly inexperienced graduate student, but I’m now neither and still believe it. Been through some shit and still believe it. Not unique or special shit, but I certainly thought so at the time.

So what started as a 50 (maybe 75)-word blog post has morphed into a 6000-word sprawling and disjointed, at times dramatic – hopefully educational – diatribe. I’m trying to deny, even as I’m writing this, that it’s a manifesto, although somebody in the Education Department will tell me it is. I hope I’m not too narcissistic and oblivious to care, although I realize I’m certainly too myopic. Perhaps I have something else, far more important, to apologize for: this advice is coming so late.

To be clear: in apologizing for the untimeliness of this advice I am not taking sole responsibility for the totality of this error. Your education system – in fact our entire social system – has failed you in this regard. That’s not an excuse, but the reality you must overcome. The good news? Your ancestors have encountered and overcome much more and your presence is the most prominent evidence of their success.

You

I think about some weird things: how you think, what you may feel, what motivates you. That’s good for me – as it helps me not to think about myself, and that’s very helpful. While I was writing this, I thought about your families: covered in chains, covered in dirt, covered in blood. Starving, boiling their shoelaces. Clothed in tatters. Misery. Clothed in yet unrealized and probably not going to be realized dreams. Hope. I try to sit there. In the hulls of ships. It doesn’t take me long and I’m back in my bed, next to my son, who has run from his room in the middle of the night screaming for his mother. My other son in the next room, waiting for a bottle that will come soon. I’ll probably have to head downstairs to warm it up so he can take it.

I wonder if John Trass was yelling, maybe screaming. Jakob probably wasn’t. It’s comforting to know – way more comforting to delude myself- into thinking he may not have. I wonder if everybody was crying. I wonder if John Trass clenched his jaw the way I do, tightening the neck and shoulders – especially on the right side – the way I do when I don’t know that my body is trying to cry. I wonder when they stopped crying for the son they never realty got to and really wouldn’t know. The one for whom America was on the tip of his tongue – on the same breath; quite literally within reach. That was embraced and pushed away; at the same time.

I think of Great-Grandma Katie Trass, who married John “Jack” den Boer. I think of her son, Robert, his son, Rodney, and my sons, one still in bed (it’s early), the other I just placed back in his crib, still whimpering.. I think of why I am writing this and why cars are driving by my house at 430.

I think of a lot of weird things.

It was a full moon last night and now the sun is rising – I can see both, close in the sky, between the trees. In the intense and confusing change of late winter and early spring. They’re close in the horizon as the night sky fades gracefully into a crystal blue morning. As the risk of sounding like Wayne Dyer (no offense to Wayne Dyer), these coincidences keep happening to me, manifesting for me, in me, with a graceful annoying persistence.

Almost always in Nature.

The link: that yours to deal with. The obtrusive thoughts, the weird thoughts. The insanity. That’s mine.

I’m now tired and uninspired. I can only allow myself one cup. I’m no longer as enthusiastic and sure that you will read the article above, or even know or (way more important) care to know about William James or John Trass or John Trass Jr. or even Jakob Trass or my sons or acting As If or reverse engineering your professional success. I almost don’t care – at least anymore – about the people in your family who died for you to be here; for your relatives that maybe you hate somehow and are haunted by. I almost don’t care that I wish it weren’t true but relieved it is. Almost don’t care that maybe I’ve planted this seed. Almost don’t care that I’ve had a role in bonding you to this now pregnant dream.

Almost.

Jung and James and Trass knew that this was the one dream that had to be realized – one that cannot be disregard and cheapened. The one that was so indelible (noetic yet ineffable) that every person colluded into conveying it without speaking. As I sit here, I’m almost nauseated by the gravity of it all.

This most powerful dream, whose power was and is so great that it could not be denied, as reflected by the most damning and conclusive evidence in existence:

You.

I know you don’t want to hear it, but I need to say it and it pains me to say it:

You.

I know that’s a great burden to bear, power and responsibility, yada yada yada, but it’s the greatest truth I know. The only one I can’t deny, a Truth so powerful It could not be denied in hull of ships, in chains, in graves.

The one that stares me in the face each Tuesday and Thursday.

You.

I got a second wind but now it’s ended.

Be yourself, but not in the way that we try to mean it. In the truest, rawest, dig for it, form.

I’m now tired and uninspired, maybe at the end of my rope, maybe at the end of my chain.

The sun has not risen above my window and I can hear my son, my hopes and dreams and fears and love embodied, my genetic expression of trauma (the working through of which) beginning to rise as well. As I hear his feet on the stairs, I think of John Trass, downstairs. I think of John Trass, junior and namesake and genetic expression.

I think of Jakob Trass, resting in bed.

I think of Jakob Trass, who died never knowing.

But mostly and inevitably, I think of You.

You can take it from here, into a void not unlike those of your forebearers. Your links. Your chains.

You, being not special or unique, but earning a place of belonging.

You can take it from here.

But take it.